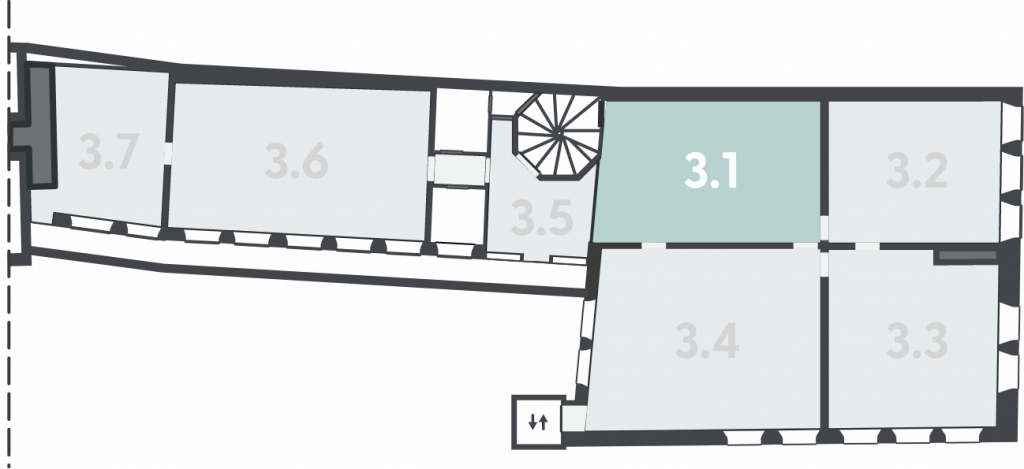

Please use the floor plan or the buttons below to select a room.

3.1 City of arts and crafts

During the city's heyday, the designation "Made in Nuremberg" was a mark of exceptional quality. Nuremberg wares found worldwide customers through a well-developed trading network. The numerous innovative inventions of the city's craftsmen became renowned as "Nuremberg wit". In this room, you can learn about the broad spectrum and the specialities of Nuremberg's crafts.

This suit of armour for foot combat is a prime example of Nuremberg craftsmanship. It was assembled from iron plates by so-called armourers. It provided complete protection to its wearer, as the plates were impervious to blades and projectiles. Great skill was required of the craftsmen to achieve a combination which gave protection as well as mobility.

The armourers were not the only ones to contribute to such a suit of armour. Polishers smoothed the surface so that enemy weapons found no hold on them. Leather craftsmen provided the numerous straps which held the suit together. Chain mail makers supplied either complete chain mail shirts for wearing beneath the plates or pieces of mail for covering vulnerable areas.

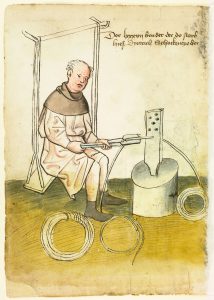

Ironworking and the arms industry were the principal crafts practised in Nuremberg. One of the inventions made in the city, the pulling of metal wire, allowed the production of high-quality chain mail and numerous other goods.

In this method, wire was pulled through a series of holes of diminishing diameter or different shapes. This reduced the wire to the desired thickness, which could be wound onto coils. These provided the material for a range of products, from chain mail to needles. At first, the wire had to be pulled by hand using a pair of tongs. Later, water power was used and a mechanical apparatus (developed in Nuremberg) to pull the wire.

While the type of armour shown here was mostly worn by common foot soldiers, it was sometimes adopted by officers as well. Our picture shows Sebald Schirmer, a Feldhauptmann (senior officer), wearing such a suit of foot combat armour in a 1545 portrait.

In addition to weapons and other elaborate objects, Nuremberg also produced everyday goods for export. The Sabbath lamp shown here is a good example. It was an object of great importance in Jewish households. The lamp would be lighted just before sunset to indicate the start of the holiday. Oddly enough, this lamp was produced at a time when Jews were officially barred from living in Nuremberg. This prohibition remained in place until the end of the 19th century.

Lamps of this type were made by the Rotschmiede, the craftsmen responsible for the manufacture of brass and brass products. Brass goods made in Nuremberg were in worldwide demand, being traded as far as Africa, South America, and India.

Guilds were an important part of urban life in pre-modern Europe. They were a way of organizing the craftsmen of a city and maintaining the quality of products. Nuremberg had no such guilds, however. Matters concerning the different crafts were controlled by members of the city council. Nevertheless, the artisans did form associations which fulfilled some of the functions of guilds, but were not allowed to have any political influence.

Certain traditions and rituals would be observed in meetings held by these associations. The welcome cup of the spice assayers is a fine example of such a tradition. It was used to offer a drink to select persons as a particular honour. This included graduated apprentices, newly accepted journeymen, or master craftsmen. Great pains were taken over the design of such a cup, as its magnificence reflected the wealth and status of the association.

The Schleifkanne tankard had a similar function: apprentices took a draught from it when they were formally and fully accepted into the community of their craft association. The chest of the grinders is another example of such a ritual object. Its design is reminiscent of a winged altar retable, but decorated with images showing the work of the polishers.

In 1596, however, painting was rated as an ordinary craft in Nuremberg. As a consequence, it was organized along the same lines as the other crafts. Painters such as Andreas Held had to serve as an apprentice for four years, and another five as a journeyman. Only then were they allowed to try their hand at a masterpiece which would qualify them for acceptance as a master craftsman. Held was appointed a master in 1690 after he had presented a painting depicting wild birds in concert. A master craftsman was allowed to establish a workshop with two journeymen and one apprentice.

Before this regimentation by the city, painting had been counted among the Freie Künste (unregulated crafts). These were separate from the regulated crafts, and not restricted to what we would consider the liberal arts today. They included a number of crafts which did not have their own regulations, such as shoemakers, joiners, armourers, or fletchers. Anyone could take up such an occupation without presenting qualifications. The lack of protection from foreign competition or dilettantes from other crafts was one reason why the painters sought acceptance as a regulated craft in the 16th century. The matter became urgent when the Reformation brought a drop in orders for religious paintings.

Painting was one craft which was basically open to women. The regulations of the Flachmaler (flat painters), however, allowed only men to paint in oil on canvas. This effectively resulted in them receiving the more prestigious and lucrative orders. Women were restricted to smaller formats and techniques such as watercolours on paper.

Special moulds were used to shape gingerbread for baking. Traditionally, they were used to create specific shapes and decorations on particular occasions such as Christmas or weddings.

The tradition of the Lebkuchen gingerbread was closely associated with Nuremberg's role as a great trade metropolis. The city's extensive trade network gave it early access to exotic spices. In addition to cinnamon, cardamom, and cloves, honey was another essential ingredient. Nuremberg was surrounded by forests, home to wild bees whose honey was gathered by the Zeidler beekeepers.

Legally, the bees were the property of the emperor. As a result, the beekeepers came under imperial control.

The Nuremberg gingerbread tradition was closely linked to Nuremberg's position as a trading metropolis. Thanks to the large trading network, exotic spices could be imported early on. But in addition to cinnamon, cardamom and cloves, honey is also an important ingredient. Nuremberg was surrounded by forest. There were many wild bees buzzing in it, whose honey was harvested by the so-called Zeidlers in the Nuremberg area. The bees legally belonged to the emperor. That is why the Zeidlers were also under imperial control.

This association is symbolized by the figure of a beekeeper (armed with a crossbow) shown on the panel below the seat of the imperial throne in the room titled "Der Kaiser und seine Stadt" (The emperor and his city)

Legally, the bees were the property of the emperor. As a result, the beekeepers came under imperial control. This association is symbolized by the figure of a beekeeper (armed with a crossbow) shown on the panel below the seat of the imperial throne in the room titled "Der Kaiser und seine Stadt" (The emperor and his city) The craft of the Lebküchner (gingerbread maker) only became regulated in 1643, before this date, it had been one of the Freie Künste, which were unregulated and had a lower status. This meant that the gingerbread was made by ordinary bakers.

CITY MUSEUM AT FEMBO-HAUS

MEDIA GUIDE