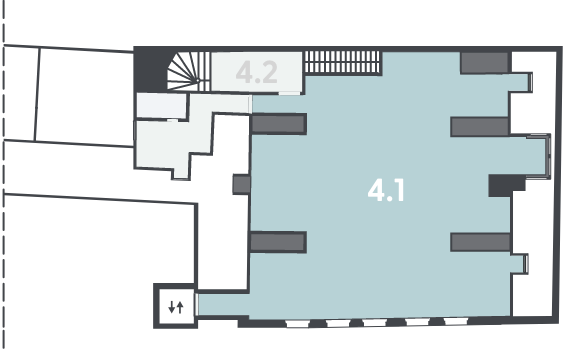

Please use the floor plan or the buttons below to select a room.

4.1 Nuremberg. Images of a City

You are now on the top floor of the house. Here, you will find a broad and varied overview over the history of the city of Nuremberg.

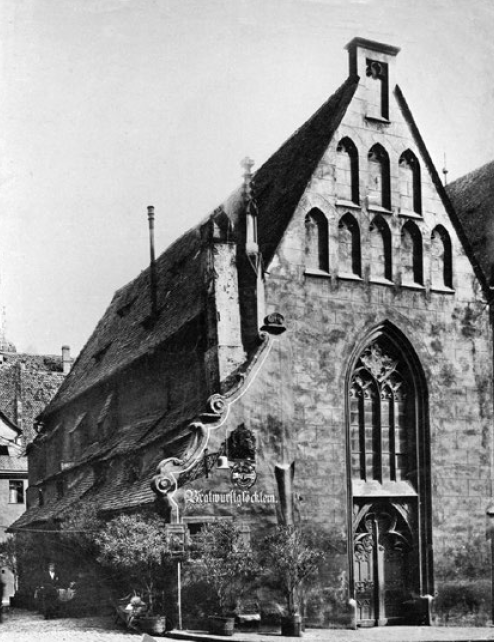

The oldest traces of human settlement in the area occupied by the modern city of Nuremberg date to the Bronze Age, some 1300 years BC. Recently, archaeological traces of a small settlement from the 9th century were found on the banks of the Pegnitz. The first written mention, however, is from the year 1050 AD, when a document issued by Emperor Heinrich III names Nuremberg for the first time. Only 200 years later, Emperor Friedrich II made the settlement a free imperial city. This meant that Nuremberg would henceforth be subject to no one but the emperor. In the 14th century, the so-called Golden Bull elevated the city to one of the central places of the medieval empire. Emperor Karl IV decreed that Nuremberg should be the site of the first imperial assembly (the "Diet") of each subsequently elected German king. The transition from Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era brought a period of unparalleled prosperity for the inhabitants of the city. Nuremberg became one of the largest and richest cities in the Holy Roman Empire. After the Thirty Years War, its former significance declined. In 1806, Nuremberg's time as a free imperial city came to an end when it was made part of the newly constituted Kingdom of Bavaria.

You are looking at a copy of what is probably the most famous piece of writing in the history of Nuremberg. This is the document in which the city is first mentioned as "Norenberc", the oldest version of the city's name. The document was issued in 1050.

In the Middle Ages as today, legal matters were recorded in writing. The Sigena Document, for example, concerns the manumission of a bondswoman called Sigena. In medieval times, bondsmen were peasants who were not considered free. Sigena was a bondswoman of one Richolf, who had decided to set her free. The manumission was carried out as a ritual act, the Münzschlag, during which a coin was struck from the hand of Sigena. This was the official sign that she was free. The manumission was carried out by Emperor Heinrich III, who was holding court in Nuremberg at the time. It remains unclear to this day just who Sigena and Richolf actually were, and why the emperor himself was involved.

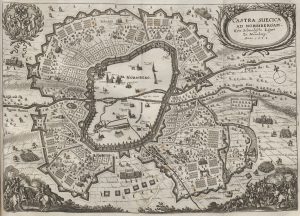

This model shows the city of Nuremberg around 1600. It was made by Hans Wilhelm Beheim, a master joiner and architect. His other works include a panelled ceiling and an impressive wooden candelabra for Nuremberg's city hall.

The city model was probably made between 1613 and 1616. The exact reason is not known, but a closer look at the model may give some hints. The city walls with the adjoining wards (the area which lies between the outer and the inner city wall) are quite conspicuous. The bastions surrounding the imperial castle are particularly noteworthy. It is conceivable that the model could have been intended as a planing tool for the city's fortifications. Such a three-dimensional model would have aided strategists in determining where and how the city could be assaulted by enemies.

Maps of the city and its fortifications were drawn up at the same time as the model. In addition, plans for an extension of the defensive works beyond the actual city walls were developed at the beginning of the 17th century, with earthworks and ditches being designed and built as a protection for the suburbs.

A close-up look:

The end of the Middle Ages saw major changes in how war was waged. Large cannon and firearms were increasingly employed. This necessitated new defensive strategies. The typical high towers of the medieval city walls were replaced by lower bastions which jutted out of the main curtain wall. The model shows the recently built bastions surrounding the imperial castle, while the remainder of the city walls is still studded with the conspicuous older type of tower.

Far from being merely decorative, city models were of great interest to enemies and spies who could read them much easier than drawn maps. The city council of Nuremberg thus imposed absolute secrecy on all those involved in the making of models and maps, and forbade their production without the knowledge and consent of the council. Major construction sites on the fortifications were covered in order to protect them from prying eyes.

This city model shows Nuremberg as it appeared in the year 1939. Some 2600 buildings are represented. Four woodcarvers worked four years to create the model.

The model was commissioned in 1935 by Willy Liebel. He was mayor of Nuremberg from 1933 to 1945 and a member of the National Socialist Party of Germany (NSDAP). The history of the former free imperial city of Nuremberg was eagerly appropriated by the NS regime during this time. The National Socialists hailed Nuremberg as the "most German of all German cities". Once a vital base of the medieval emperors, the city was now reinterpreted as a "Führerstadt" closely associated with Adolf Hitler. A reconstruction of the medieval appearance of the old town was considered imperative. Modern buildings, billboards, and chimneys were removed. The main synagogue on the Hans Sachs-Square also fell victim to Nazi anti-Semitic ideology. It was demolished in August 1938. Today, a stainless steel model fills the gap in the model which is displayed here.

When the model was first presented, Willy Liebel had remarked that it should be considered a "testimony of its era" which would be "admired for centuries to come".

While the old town was undergoing this transformation, the huge area of the Nazi Party Rally Grounds (not visible on the model) was laid out on the south-eastern outskirts of the city. Here, the Nazis envisioned an enormous field and huge monumental structures for their party rallies, to built under the direction of Albert Speer. The site was never completed, however. Today, only the unfinished Congress Hall and the grandstand of the Zeppelintribüne remain as testimony of the Nazis' architectural propaganda.

A close-up look: The so-called reconstruction of the old city

According to the National Socialists, the so-called reconstruction of the old city was intended to restore what they perceived as the medieval appearance of the city. Modern elements were removed if they did not fit in with the ideological preconceptions of a medieval cityscape. More than 400 buildings were thus altered. It depicts Nuremberg's appearance in the 1930s – and not the actual medieval city.

The large square of the Hauptmarkt at the heart of the old city can easily be discerned on the model. The elaborate Neptune Fountain, donated by Jewish patron Ludwig von Gerngros, was removed from this marketplace in June 1934. A year earlier, the donor plaque had already been secretly removed due to complaints about the Jewish patron.

After three years in storage, the Neptune Fountain was re-erected on the Marienplatz square (in front of the NSDAP Gau headquarters). The removal of the fountain from the Hauptmarkt had created a large open area which could be used for rallies of uniformed National Socialists. The medieval cityscape thus became a backdrop for the staging of Hitler's Germany. It is hardly surprising that the Hauptmarkt was renamed Adolf-Hitler-Platz during this period.

At the end of World War II, Nuremberg resembled a wasteland. The allied air raids had destroyed the old city almost completely. More than 6000 people had lost their lives, and more than a quarter of the population were homeless. The Fembo-Haus had lost its rear and side annex buildings to the war.

Reconstruction began as soon as the enormous masses of debris had been cleared away. It was quite another task to fill the city with life again. The Opera resumed its musical programme shortly after the war was over. The city's popular fairs resumed in 1947, and the Christkindlesmarkt reopened a year later.

The activities of theatres and societies received a boost when the entrepreneur Theo Schöller built the Buchersäle venue. His Schöller company, which produced ice cream, thrived in post-war Germany. The brand logo was omnipresent on the awnings and deep freezers of shops and newspaper stalls. Theo Schöller is a prime example of the rapid reconstruction and economic regeneration of the city.

In more recent years, the Theo and Friedl Schöller Foundation has contributed significantly to the remodelling of the municipal museum, which would not have been possible otherwise.

So much for this section of the exhibition. If you want to learn more about the history of the free imperial city of Nuremberg, please proceed to the third floor.

Once there, you will have to pass through the first room (which deals with arts and crafts) to reach the second room behind it and continue the tour.

CITY MUSEUM AT FEMBO-HAUS

MEDIA GUIDE